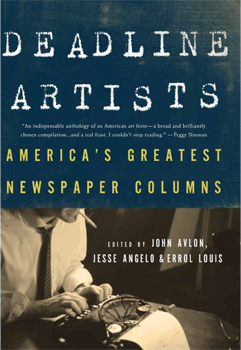

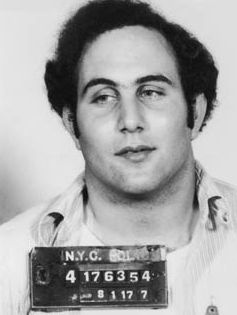

[In the summer of 1977, a serial killer terrorized New York City. Initially known as the .44 Killer and then as the Son of Sam, the murderer communicated with Daily News columnist Jimmy Breslin through a series of letters. In the end, David Berkowitz was caught and sentenced to six consecutive life terms in prison.]

[In the summer of 1977, a serial killer terrorized New York City. Initially known as the .44 Killer and then as the Son of Sam, the murderer communicated with Daily News columnist Jimmy Breslin through a series of letters. In the end, David Berkowitz was caught and sentenced to six consecutive life terms in prison.]

At night, on the way home, there was a stop at the 109th Precinct, which is housed in an antiseptic brick building that removes a part of the terror and all of the glamour of being in a police station.

On the wall of an upstairs office was a color photo of a gun, a black gun with a brown handle, and some brass cartridges placed against a sky-blue background. The printing on the picture said this was New York crime lab Case No. 771663. The gun is a .44-caliber Bulldog. Somewhere on the other side of the closed metal Venetian blinds, out in the night-empty neighborhoods of the city, was a guy with frenzy in his eyes and a .44-Bulldog in his pocket. He shoots at young girls with brown hair. In doing so, he has killed five people and wounded four others in the last nine months.

He shot two of the girls within six blocks of my house and the streets where I live are totally deserted at dusk. I know one girl, Mary Benot, secretary, who now wears a blond wig over her brown hair. She says a lot of girls she knows are doing the same thing. Nobody would be cheered by the chart which was on the wall alongside the picture of the gun. The chart said: “Weapons stolen, 667. Stolen weapons checked, 4.”

The man in charge of the investigation, Timothy Dowd, an inspector, sat at his desk and answered telephones. Dowd looks much younger than his 61 years. His blue eyes stared at the door as he listened to the phone, said it wasn’t enough. On a windowsill, 17 hand radios sat in slots in a recharging machine. This probably is as big an investigation as the New York police have ever run. And Dowd, after hanging up the phone, said it still wasn’t enough.

“We need a phone call,” he said. “We’re doing everything we can. We’ve got the best homicide men from all over the city working here. But it surprises us we don’t hear from the family or from relatives of the killer. Somebody must live with the guy and suspect something.” In leaving the room, the eye was attracted by a large stenciled sign above the light switch. In that great police subtleness, the sign above the light switch said: “Turn Off Lights.”

We took a cab home. As we passed the place where the killer shot one of the girls, I saw a big guy in a zippered jacket standing with his hands in his pockets. He is a detective I’ve known for years and I had the cab stop and I got out.

“Getting the feel of the thing?” I said to him.

“That’s television s—-” he said.

“Well, what do you come out for?”

“Because I’m just starting on the case. I always start at the start. Go to the scene and start walkin’ from there. I don’t even know the names of the people who got killed. Only name I’m interested in is the name of the man done the killin’. I’d give up a month’s drinking if you could arrange the meetin’.”

He has spent his life in the slum precincts and his speech patterns come from those streets. “Come on,” he said. “We walkin’.” And he started down the street, a gun and a radio in his pocket, a man who has spent his life hunting on cement. His target this time is not the ordinary homicidal person we grow so quickly in the slums. The .44 killer is one of those special, twisted people who have been with us through the ages.

He began walking down a street which goes along railroad tracks. There was not a person in sight.

“Look at these lights they got on the houses,” he said. “Little carriage lights. That’s about as much illumination as you get from my lighter. I could hide nothin’. These murders never could happen in a black neighborhood. Too many people out on the streets. Everybody would see who did it. Man we after is only workin’ white neighborhoods. Nobody comes out at night and he can prowl around and catch him a stray girl and do what he has to do.

“Look at these people around here,” he said. He waved a hand at a row of attached houses running into an apartment house. It was 11 p.m. and the only sign that there were people inside were windows filled with the pale blue light of television.

“These same people here, you put a lot of kids on the streets here makin’ some noise, and these here people call up and complain. If they got any sense, they pay kids to hang out on the sidewalks all night. Hang out and bang garbage cans around. No killer goin’ walk around, if you got people out on the streets.”

Up at the corner, a man appeared. He was holding a German shepherd on a leash. He stopped as he saw us walking toward him.

“Look at this,” the detective said.

The man with the dog bent down and unleashed the dog. He stood there with a hand on the dog.

“I’m continuing to walk by and the dog’s goin’ to continue to sniff,” the detective said. “If the dog don’t continue to sniff, he goin’ be a dead dog.”

The man put the leash back on the dog and stepped out of the way and we went past him.

When we got down to the boulevard, there were some people at the coffee shop and a few coming out of the subway. But much less than normal.

“We got a Jack-the-Ripper case and everybody thinks they’re better off hidin’ inside the house,” the detective said. “All they do is make it easier for this guy to go around killin’ people. Black people the only ones who know what to do about crime. The more people outside the house, the less can happen to you.”

He turned around and walked away from the boulevard and back into the dark vacant streets where a killer has hit twice and where people are afraid he will soon hit again. This time, as the detective walked, there wasn’t even a man out with a dog.